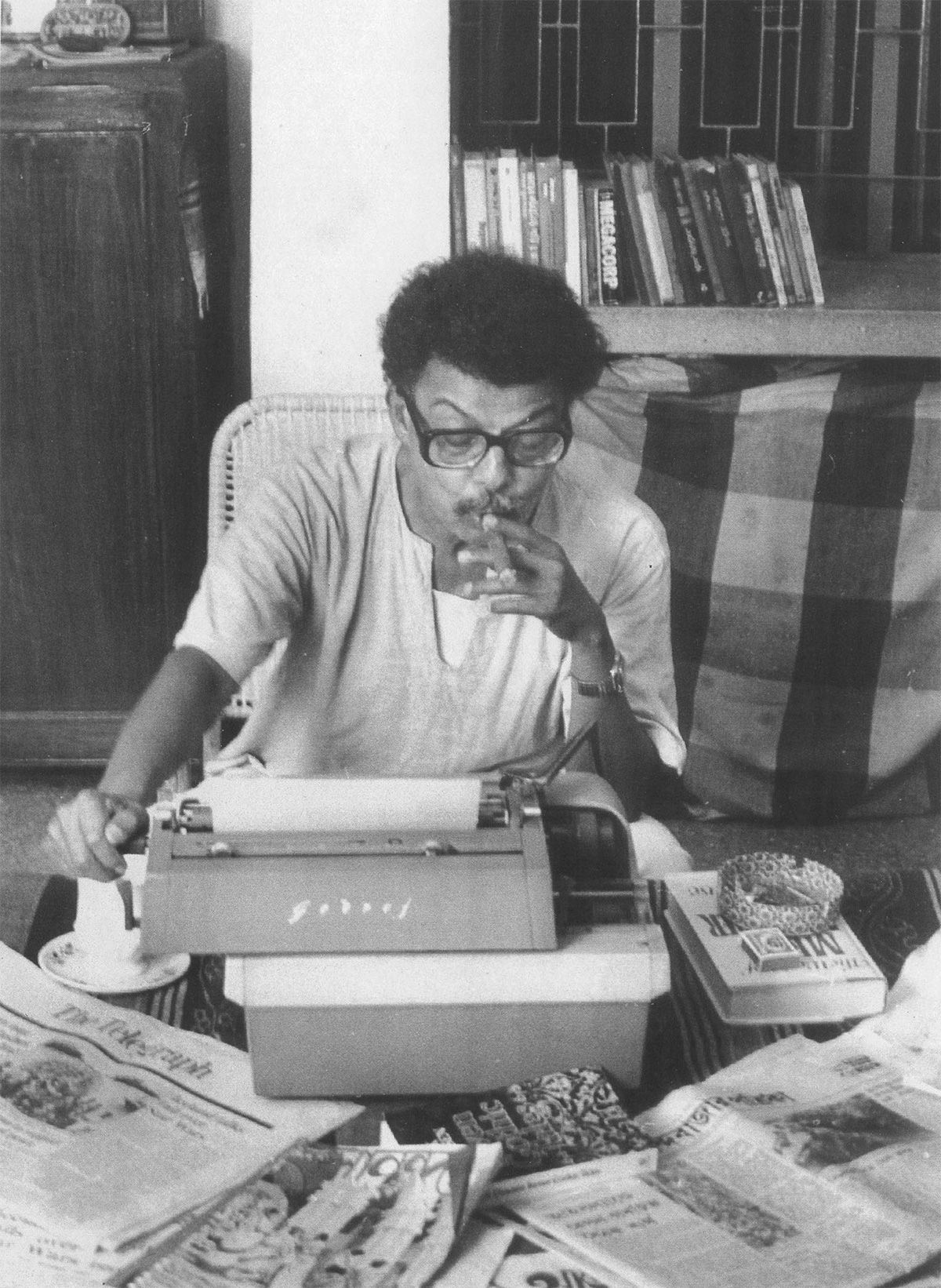

"When I write. I always think of the ordinary people. A writer must always seek for the truth if he is to be honest to himself and to mankind. Truth was and still is my weapon," Ghosh had noted.

Ghosh doffed many professional hats before committing to his career as a scribe. He worked as an electrician, a waiter in Dhabas (local eateries), a salesman of pharmaceutical goods, proofreader, a member as well as a manager of a dancing group, among other odd jobs. His formal education had to end at the Intermediate level, but he rose to prominence as one of the most influential editors, writers, satirists, and novelists in Bengal despite his lack of a formal higher education.

In 1941, with only a high school education, no special skills, and his mother and sisters in Nabadwip to support, Ghosh took the first job he could find in Calcutta, as an electrician's mate. The work was not steady and paid only four annas a day (an anna or ānna was a currency unit formerly used in British India, equal to 1⁄16 of a rupee).

After four months he found regular work as an apprentice viceman fitter with a small company where he got paid ten annas a day, he sent six of which to his mother and lived on the remaining four. He saved by eating at a Muslim restaurant for the poor where he was allowed to sleep in a corner in exchange of certain odd jobs around the place. When asked why as a Hindu he did not choose a co-religionists establishment he had responded, "Because Hindus would ask why I was there, what my caste was and so on, but the Muslims never asked anything; they were more human."

As soon as he was well enough, Ghosh returned to his ancestral district of Jessore to seek work and was hired as a road sirkar (foreman) for a construction firm building a large airdrome.

However, he lost that job after three months when the police discovered that he was a member of the Radical Democratic Party. He was held in custody for 15 days, and then expelled from the restricted military area.

Ghosh went back to Nabadwip and with the help of his maternal uncle, was admitted to the Intermediate Science Class of the wartime Nabadwip branch of Vidyasagar College of Calcutta. He disliked the classroom environment and soon stopped attending classes. But he remained active in student politics and helped form the Radical Students League.

In Calcutta, Ghosh worked briefly as a dishwasher in a restaurant and later as an agent selling pharmaceuticals, buckets, cardboard and insurance on a commission. Then he managed a touring troupe of Kathak dancers; interpreting the Kathak dances of North India to Bengali audiences, arranging travel and housing for the troupe and selling tickets for the performances.

His first poem was published in early 1940s in Purbasha (The East Horizon), a Calcutta periodical edited by Sanjay Bhattacharya. In 1944 and 1945, he occasionally contributed personal articles to his party organ Janata (The Mass). Soon his poems were published in magazines like 'Dwandwa' and various contemporary ones.

He returned to Calcutta and joined the Indian Federation of Labour. He was drafted by the Radical Democratic Party to go with a cadre to organise jute workers in the industrial area of Barrackpore. During his five months there, he was severely beaten by communist workers for speaking out against their platform and their candidate.

With the end of the Second World War in September 1945, trade union activity increased. In early 1946, Ghosh was assigned to organise the Lalmanir Hat branch of the Bengal and Assam Railwaymen's Association. When the police evicted him from Lalmanir Hat, which was then under British rule, he crossed the nearby border into Cooch Behar, then one of the princely states ruled by a maharaja. While the Lalmanir Hat police were going through the procedures required to request the maharaja's police to evict him, Ghosh continued with his work.

"I was just going back and forth across the border and doing my job. For five months I played this game."

Next, Ghosh was sent to Darjeeling to bring the organiser of the workers on the Darjeeling-Himalayan Railway into the party fold. He later realised that the union wanted to factionalise the workers and was working with the company to oust the organiser. The union eventually accomplished this by giving him a pompous title in the overall organisation, whereby he lost control of his local group. The organiser became Ghosh’s friend.

Ghosh noted:

"The net result of this experience is a story, named after the organiser, Sagina Mahato, which tells how a Marxist organisation destroys a natural labour organiser. No personalities can be tolerated. Never! Instead I had to set up a faceless organisation. I wrote seriously about this tragedy of his. Before that I was writing shallow things and nobody was really paying attention. "

First published in Desh magazine in 1956, Sagina Mahato, a story written by Gour Kishore Ghosh in remembrance of his colleague from his political activist past, was successfully adopted into movies. The Bengali (SaginaMahato) andHindi (Sagina) versions were directed by acclaimed filmmaker Tapan Sinha, with the famous thespian Dilip Kumar playing the part of the protagonist SaginaMahato in both instalments.

Official start in journalism :

Ghosh’s introduction to journalism came in early 1947 in Calcutta when he became a proof-reader for a new weekly literary magazine called Nababani (New Message), which survived for only one year. He also wrote for the newspaper in an informal capacity, from his own fictional stories and poems to national and international news to fill the pages of the paper.

Thereafter Ghosh found work as a petty clerk in the land customs clearing office, which had been created to handle traffic across the new border between West Bengal, India, and East Bengal, and Pakistan. From his salary of ₹30 per month he sent ₹20 to his mother, but couldn’t “even rent a bed in Calcutta” and on the remainder.

Rescue came from a fellow radical humanist, Samaren Roy, who let Ghosh sleep in the room where Roy was printing his weekly political magazine Arani (name of the wood used to spark a fire by rubbing two sticks together). Ghosh met Roy once a week on Saturdays when the magazine was published and Roy would prepare for the next issue. Henceforth, Ghosh was regularly writing short satire stories for the magazine, sometimes doing a little proofreading to help out Roy, all this while he was still working at customs. Ghosh also started working on his own first book at this point. Arani however had been closed down in mid-1948.